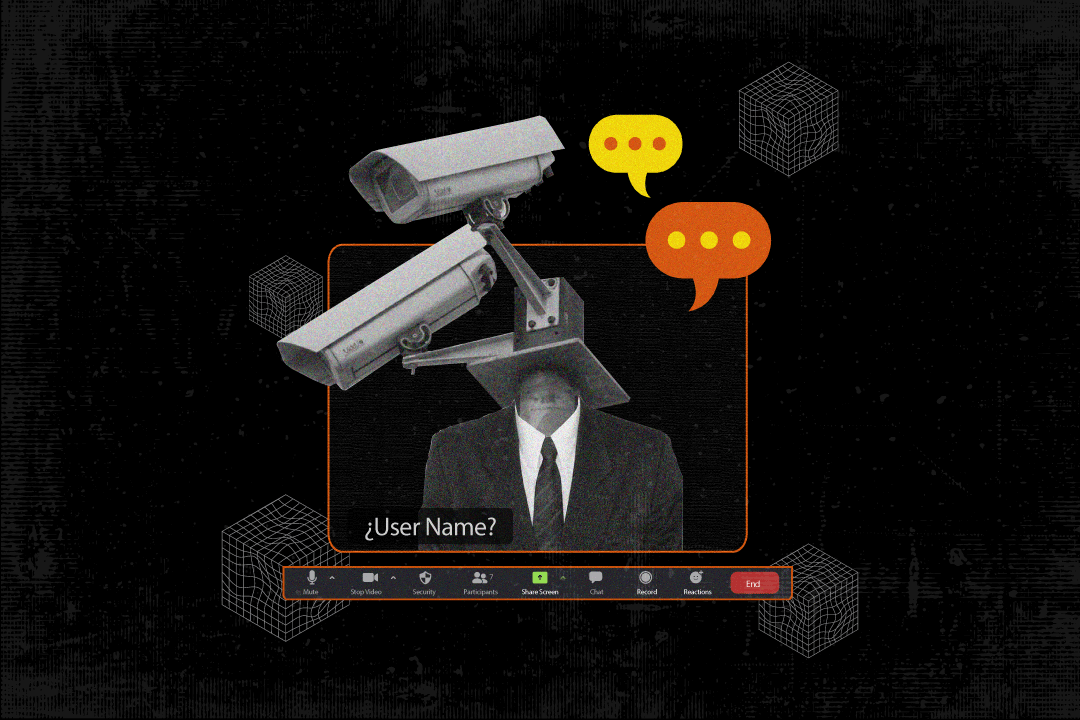

The Undercover Computer Agent in Ecuador

By Alex Sotomayor

Background

After the 2001 terrorist attacks in the United States, policies related to the protection and safeguarding of national security went through strong modifications. Since then, almost every country that calls itself democratic or not, has designed its public policy based on the protection of state and/or citizen security through surveillance mechanisms. In this line of thought, the speech of political power on the technification of security seeks to legitimize public action through an argument centered on the idea of technological effectiveness and neutrality.

On the other hand, in Ecuador, the criminal incidence has increased significantly in recent years, mainly due to the active presence of criminal groups linked to Mexican and Colombian cartels, placing the country as a prominent regional epicenter for a multiplicity of crimes and organized crime. With this background, it is foreseeable that citizen perception regarding the use of surveillance mechanisms to “improve” security conditions is favorable and therefore, legitimized.

In this context, the undercover digital agent emerges with the narrative of being a crucial element in the pursuit and investigation of criminal activities. For this reason, the legislature incorporated this figure in the Comprehensive Organic Criminal Code (COIP) through the Organic Reform Law to various legal bodies for the strengthening of institutional capacities and comprehensive security, published in the Official Registry Supplement 279 of March 29, 2023.

In this way, article 483.1 is adhered to, legally enable the undercover agent, who, in simple terms and seen from the “duty” of his existence, is a public servant of the Comprehensive Specialized Investigation System of Forensic Medicine and Forensic Sciences whose purpose, like a traditional undercover agent, is to infiltrate criminal groups with the aim of collecting information, dismantling illegal operations and preventing future criminal attacks.

The purpose of this analysis is to break down the exorbitant powers that were granted, through the semantic and syntactic ambiguity of the wording of the norm, as well as to reveal the problems of scope, temporality and the obvious conflicts of this figure with the fundamental rights of privacy and intimacy of people, also emphasizing the arguments that make the wording of this norm clearly unconstitutional.

Ambiguity problems

As it was already mentioned, article 483 of the COIP authorizes the covert operations of the “undercover digital agents so that they can carry out investigative management tasks hiding their true identity or assuming an alleged identity, for which they must carry out patrols or digital actions in cyberspace, penetrating and infiltrating computer platforms such as forums, communication groups or closed sources of information or communication, with the purpose of tracking people, monitoring things, making controlled purchases and/or discovering, investigating or clarifying criminal acts committed or that may be committed using communication technologies or against them. In the development of their activities, the undercover digital agents may exchange, directly send files, files with illicit content or apply techniques to preserve and decrypt information collected that is useful for the investigation. (…) Identify the participants, gather and collect information, elements of conviction and evidence useful for the purposes of the investigation. Additionally, they may obtain images and make audio or video recordings of the conversations that they could have with the person or persons investigated, depending on the nature and modus operandi of the organization, with the use of any technological means, anywhere, for which the prosecutor will previously obtain the respective judicial authorization”.

Firstly, the undercover agent can infiltrate cyberspace with the purpose of “surveilling things”, with this very open and ambiguous wording the sphere of surveillance to which the agent can access is not delimited, thus enabling them to act as a “Black Hat” or cybercriminal in the broad sense; using techniques such as DDoS attacks (Distributed Denial-of-Service Attacks), and may use spyware, social engineering techniques, etc.

The law also establishes that the undercover digital agents could “…discover, investigate or clarify criminal acts committed or that may be committed using information and communication technologies…”. This ambiguity allows the figure of the undercover agent to be used with broad discretion and subjectivity, opening the door to mass surveillance. Furthermore, the rule enables the undercover agent to anticipate the commission of criminal conduct, in contradiction with the nature of computer crimes given that by their nature these are crimes of result and not of mere activity.

Nor is there a limit on the time that a person will be monitored or what investigative management tasks will be applied so that the undercover agent can do their job.

It’s also a disproportionate measure to grant the undercover computer agent the possibility of obtaining images and making audio or video recordings of the conversations that they may have with those investigated with the use of any technological means and in any place. The investigation space no longer has any limits and it’s not detailed which means are suitable for this operation, nor what happens with third parties who have nothing to do with the investigation and who simply participate in the conversation. It could be understood that the undercover agent is equipped with all the necessary equipment and that they will apply techniques for filtering citizens’ information, however there is no clarity about the cases to which they should be applied and the limitations to avoid the violation of the rights to privacy, the protection of personal data and the inviolability of correspondence. For these same reasons, after the General Data Protection Regulation (EU) 2016-679 became effective, the European Union issued the Directive (EU) 2016-680, focused on data protection in the criminal field, with the objective of preventing violations of the rights and freedoms of citizens. Therefore, it’s evident that the reform is not aligned with international legal instruments for the protection of personal data or with internal regulations.

Problems of Applicability of Covert Operations in Ecuador

The Regulation for the application of monitored or controlled entries, established by resolution 091-FGE-2015, has turned out to be impracticable due to its disconnection from operational reality. Although it proposes ambitious initiatives such as a school for Undercover Agents, identity modifications and inter-institutional collaboration, it lacks the practical means for their implementation.

The main deficiencies include the lack of budget allocation, the absence of effective coordination between state entities and the lack of security protocols for the management of confidential information. These limitations have prevented the administrative body from implementing the organizational structure necessary for covert operations, failing to comply with the 60-day period established after its publication.

In essence, the Regulation lacks a comprehensive operational plan covering administrative, human resources, legal and budgetary aspects, which has hindered its effective implementation to date.

In this sense, since there is no coherent and transparent regulation that determines and delimits the execution of covert operations of any kind; The state is given an open letter to execute surveillance mechanisms arbitrarily.

Unconstitutionality of the norm

In the case of Fontevecchia and D’Amico vs. Argentina it was determined that the use of surveillance techniques as an interference in private life must be suitable, necessary and proportional, and that in addition, this assessment must be carried out on a case-by-case basis. The figure of the undercover digital agent has a scope of interception of communications and surveillance that is exorbitant and its limits are few, which could imply an incompatibility with the guarantees of the right to privacy and inviolability of correspondence. The law is arbitrary, since it grants a high margin of discretion to FGE to intervene in communications and access the privacy of a subject in any type of crime classified in the COIP, or due to the ambiguity of the aforementioned rule, even for the “prevention” of crimes, without verifying that the interception is necessary or pursues a legitimate purpose in the specific case. Furthermore, there are no mechanisms that guarantee the destruction of information when it isn’t relevant to the case. This type of investigation could even be allowed at a very early pre-procedural stage where there are still no real indications of an investigation.

Suitability

Regarding suitability, interception as an investigative measure seeks to obtain evidence of the materiality or responsibility of a crime. This technique allows the surveillance of alleged perpetrators or suspects and allows the FGE to obtain relevant information regarding an infraction and prevent the commission of others. However, since there is no transparency in the intervention mechanisms, it can’t be concluded that this is a truly effective measure, especially in digital environments, so it’s not concluded that this measure is suitable and appropriate for crime prevention.

Necessity

On the other hand, the necessity criterion seeks to verify that a State measure does not reduce a right more than is necessary for the State to effectively achieve the constitutional goal it proposes. Due to the ambiguity in the wording of the rule and since it allows the undercover agent to intervene in any type of crime, it is potentially intrusive that interception can be applied to infractions that do not have the same seriousness, penalty or severe social repercussions, such as drug trafficking, organized crime, murder, sexual violence, bribery, embezzlement, concussion, among other crimes. Furthermore, as surveillance is carried out secretly without notification to the subject under investigation, the risks of arbitrariness increase, making it crucial that the rules governing this measure are clear to protect against discretionary use of interception. It’s deeply unnecessary to use this investigative technique to achieve the constitutionally intended objective. It should be especially considered that accessing a person’s intimate life is justifiable as long as there are no other conventional investigation mechanisms that allow the crime to be detected or that seek to identify its authors or accomplices; additionally, interception must be used if and only if it serves the purposes of the investigation in relation to the importance of the crime and its seriousness.

It is necessary to highlight that it is the prosecutor’s office that authorizes the interventions of the undercover digital agents, therefore they are not exempt from providing sufficient reasons to justify the surveillance in light of the reasonableness requirements. The prosecutor should consider, among others: 1) the nature of the crime investigated, 2) precautions regarding the use of the information obtained or the circumstances under which the interception is to occur.

Proportionality in a strict sense

This requirement seeks to verify whether there is a due balance between the constitutional protection of privacy and inviolability of communications and the restriction made by the incorporation of the figure of the undercover digital agent. Undoubtedly, surveillance represents an intrusion and interference in private life. However, it is difficult to abstractly determine the benefits or costs of such a measure, so the proportionality analysis must be carried out on a case-by-case basis. Consequently, in the specific context of an investigation, it’s up to the judicial authority to first evaluate the relevance, adequacy, necessity and proportionality of the measure, balancing the rights at stake. In addition, it must ensure that the measure does not violate the prohibitions and limitations established by law, such as interception in cases of professional secrecy or to avoid the revictimization of minors, among other scenarios.

Conclusions

After the Edward Snowden revelations, the “Necessary and Proportionate: International Principles on the Application of Human Rights to Communications Surveillance” was created, which establishes principles to ensure that communications surveillance respects human rights. These principles include necessity, proportionality, transparency and judicial supervision, among others. Since privacy is a fundamental human right and is essential for the maintenance of democratic societies, it’s evident that any restriction on the right to privacy, including the surveillance of communications, can only be justified when it’s prescribed by law, necessary to achieve a legitimate objective and proportional to the aim pursued.

Applying this measure in the way it is currently stated does nothing more than legitimize the Attorney General’s Office (FGE) for surveillance and intrusion into privacy, since it grants it invasive and exorbitant powers, given that it can carry out these investigations without the need for any type of judicial authorization and, even without there being a crime. Due to the inapplicability and ineffectiveness of the current regulation, only by means of a judicial resolution the supossed identity should be granted by mentioning the real name of the agent and the false identity confirmed for a specific case, the authorization for patrols and digital actions in cyberspace and the obtaining and transfer of information resulting from the investigation, because otherwise the FGE can, without being in the framework of an investigation, interfere in the communication, storage and even the thinking process of any citizen, without also establishing which would be the parameters of judicial control and scrutiny so that the judges to whom this measure is requested can establish its adequate reasonableness with protection of the rights to privacy and the protection of personal data. The figure of the undercover digital agent whose constitutionality is questioned implies an unnecessary and disproportionate impact on trying to guarantee the prevention of crimes, due to arbitrary interference with privacy and non-compliance with international treaties and internal regulations. Due to the lack of legal guarantees for the protection of people’s privacy, the population must seek de facto mechanisms, such as the use of encryption and anonymization techniques, since this is the only thing that guarantees the protection of our data.